There is a pattern that emerges when church folk discover my passion for tabletop gaming culture and the people that inhabit it. I can generally trace the arc from the moment the conversation starts. It is mostly honest inquiry, but occasionally the arc jumps to a place of confusion, fear, and sometimes even anger. The place where it goes off the track almost always happen shortly after I tell them I have played Dungeons & Dragons for years, and still do.

If you are reading this as a gamer who either professes faith yourself or just has experience with church folk, you can probably recite the questions I will now recount – questions, word for word, I have been asked within the past year:

- “Isn’t that a game that teaches you how to do real magic?

- “Doesn’t that game glorify demons?”

- “I’ve heard that game has made people kill themselves. Is it safe for my kid to play it?”

We have already addressed the “Is it ok to play D&D as a Christian?” discussion before on our podcast and in previous articles. But how did we get to a place where such ideas needed to be addressed? What made the Church decide it needed to take arms against a game people have been playing for decades? It is time we address the importance of exploration, context, and conversation rather than rely on knee-jerk reactions. To quote George Bernard Shaw, “Beware of false knowledge; it is more dangerous than ignorance.”

While Dungeons and Dragons was created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in 1974, it was not until the early to mid-80s that it began receiving its dark reputation. That time has been since labeled as a ‘moral panic‘ – referred to simply as “the panic” among gamers that lived through it. Organizations like “Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons” (BADD) and individuals like Jack Chick began taking to the streets (and the courts) with the message that the game was killing the children. While men and women of faith have been a part of the game’s creation and development from the start – the Church rallied to the their call.

Perhaps the most often sited example of this danger was the tragic death of James Egbert. While attending school at Michigan State University, Egbert swallowed a number of pills and entered into the school’s steam tunnels hoping to end his life. He was not successful, and shortly after he recovered, he went into hiding at a friend’s house. His parents were convinced that their son could not have made such a decision on his own, and hired a private detective to investigate their son’s attempted suicide. It was this detective, William Dear, who first theorized that it was Dungeons and Dragons that caused Egbert to attempt suicide.

In 1979, Egbert called Dear from Louisiana. He had attempted to kill himself again and failed again. He let Dear know where he could find him, and the private investigator picked him up. Dear was sworn to secrecy and brought Egbert to an uncle he could stay with. For a while, everything seemed set to right, but that was not the end of the story. In 1980, Egbert died as a result of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Dear would eventually recount all of this in a book he wrote about the incident, published in 1984, entitled The Dungeon Master.

No one can know for certain what caused Egbert to want to end his life. Maybe it was the pressure of being a child prodigy entering into university at the age of 16. Perhaps he was bullied by peers, or suffered from undiagnosed depression, or any of a dozen different triggers that lead him down that road. Yet the idea that it was caused by a game that he did not even play anymore at the time of his death is not among them.

In the same year as Dear’s book came out, Jack Chick published a black and white evangelistic tract called Dark Dungeons. It featured the story of two Christian girls entering their freshman year of college. While at a party, they were drawn to the appeal of role playing games – which apparently all the most popular and influential people at the school were involved.

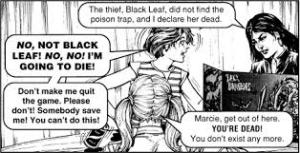

As their characters grew more powerful, their grades plummeted. All the while, their dungeon master, Ms. Frost, encouraged them both to go deeper and deeper into the game. When one of the girls reached level eight, Ms. Frost taught her how to do real magic – and she begins casting spells on her professors. When the other girl’s character, a thief by the name of Blackleaf, died in the game, she was shunned. With Blackleaf dead, the girl had nothing left to live for, and killed herself. According to the tract, both girls would have probably shared the same fate – but the other girl sought the aid of a local preacher who freed her from the demons of RPGs. The last frame of the tract shows her in a circle of people signing and praying around a bonfire of gaming books.

Image taken from the Dark Dungeons tract. The entirety of the tract can be viewed at the Chick Publications site

When we heard that Dark Dungeons had been licensed for a film, We talked about the after effects of it. Would this be a rallying cry bringing back the bad old days of the panic? Would it point a satirical blade at the Church to make us all look like fools? No one knew for certain – but everyone asked. Thus, I made a point of getting myself to the film’s premier to talk with a number of people involved in the film’s creation. You can hear some of those talks here, but there is something deeper that lives in this movie. Something that has me urge Christians – whether they are gamers or not – to watch this film.

I wish to be perfectly clear. We at InnRoads have and continue to acknowledge that there are those who have an unhealthy relationship with gaming. We understand that there are many reasons why someone may feel uncomfortable with the hobby on a personal level, as it would draw them away from their relationship with God. We even allow for the fact that there are people who have had bad experiences with role playing in the past and assume that it was because of the game itself. Even so, it is still our thought that this movie is something Christians should be watch for a number of reasons. Some practical, some philosophical, and all out of a sincere love of the hobby and the people who are in it.

This can’t be what we show people

This movie does not mock Christians, Christianity, or the Church. They took pains to ensure this. It is merely a frame by frame recreation of the Dark Dungeons tract. However, I stood in line to get my copy. I sat in the crowd at the premier. And I can say that there are people who see this movie and say “Look at these stupid Christians.” It is not the movie’s fault. It’s ours.

For many of the people who have this reaction – we have given them no reason to think anything different. There is an old guard who remembers the panic. There are new players of all ages who have been assaulted by Bible waving preachers and family members who have never seen the game being played. While we are just one of a growing number of organizations that look to speak God’s love into this community – as a body, we have failed to show them anything other than what they see in this movie. We cannot let that stand.

Do you ACTUALLY think this happens?

This simply isn’t real.

I have played D&D for years. I have played characters well past the eighth level. And I am here to proclaim to you that I have never cast a REAL spell in my life, nor have I been offered an opportunity to learn. I can also tell you that I’ve had characters die. Yet my first thought has never been “How can I go on?!” nor has any group I’ve played with ever said “Leave – you do not exist.” They usually hand me an empty character sheet and say “What do you want to play next?” Long before any of this, however – you can tell that this tract/movie is based on a lie the moment one of the characters says, “Those are the role-players. We’ve tried to stop them, but they’re just too POPULAR!” I have an entire lifetime of examples to prove to you that this is simply not true.

The questions I still get today are most often not based in personal experience, but in hearsay and postulations popularized by this tract and others like it. I challenge you to watch this movie. As you do so, watch this faithful adaptation to the source material and ask yourself, “Do I actually think this is what happens?”

It is time to talk about this

Thankfully, I have spoken to a number of gamers who were not even aware that these issues still exist. The old guard battling against the assumed sin and decadence of role playing games are being replaced by those who are open to storytelling akin to Tolkien, Lewis, Chesterton, and other faithful Christian authors using myth and faerie tales to demonstrate godly character. I look forward to to the day that I stop having to answer the “isn’t that demonic?” question all together.

But is this just one tip of a much larger issue we still need to address?

It is time to stop pointing fingers. It is time we stop looking at media, stereotypes, and other assumed evils as the lynch pins that stop people from being good, decent, God-fearing folk (read as: ‘just like me’). We need to do away with the assumption that our sons and daughters will grow up right because we keep them in a flannel-graph world that knows nothing of sex, violence, and naughty words. The world is complex, people are complex, and- while we don’t want Him to be- God is complex.

What a game of D&D actually looks like.

From the film Zero Charisma – also worth watching

It is time we stop creating mustache-twirling villains. Instead of trying to stand up to defend God against a sea of perceived evil, perhaps we should be looking to stand with God to care for His children. It will call us to be uncomfortable, to be open, and to be willing to put in real time in the mess of human existence. It might even mean discussing a movie with a gamer that’s been hurt by the Church, or gathering together with some friends to tell stories while rolling dice.