Legacy games started with a reworking of Risk in 2011. Risk Legacy introduced a progressive revelation of playable factions and other game elements hidden in envelopes and boxes. It also created a persistent mechanic where the last game you played will have a direct impact on every game played after it. I had lost interest in traditional Risk years before, but when I heard the stories of capital cities being raised and nuclear fallout rendering once proud nations useless – I came running back to see what this was about.

Legacy games started with a reworking of Risk in 2011. Risk Legacy introduced a progressive revelation of playable factions and other game elements hidden in envelopes and boxes. It also created a persistent mechanic where the last game you played will have a direct impact on every game played after it. I had lost interest in traditional Risk years before, but when I heard the stories of capital cities being raised and nuclear fallout rendering once proud nations useless – I came running back to see what this was about.

T.I.M.E. Stories created a modular system of storytelling that many have applauded for its innovation. Pandemic Legacy has become a force of nature in the gaming world. It was heralded by many as the best game to come out last year – rocketing to the top spot in the rankings at Board Game Geek even in spite of a concerted effort to vote it down. This does not even address games that are campaign length card games that take place in worlds like Warhammer, Pathfinder, and Shadowrun.

What is it about legacy gaming that grabs people? I know of few people who would call Risk or Pandemic bad games, but they also are not frequently played. The bulk of the criticism I’ve heard talks about how they’re just showing their age. The greater gaming world had just moved on to other, shinier prospects. They were games of the past, part of gaming’s history. So what better to bring them back than to harness the power of history.

What is it about legacy gaming that grabs people? I know of few people who would call Risk or Pandemic bad games, but they also are not frequently played. The bulk of the criticism I’ve heard talks about how they’re just showing their age. The greater gaming world had just moved on to other, shinier prospects. They were games of the past, part of gaming’s history. So what better to bring them back than to harness the power of history.

There’s a phrase I throw around liberally when I talk about the way we do ministry at InnRoads. We are about the business of helping people create a common history. Since the days we started gathering around fires and telling stories of the old days, shared experiences have tied us together. Nostalgia has been made into a commodity to be traded because we link people, places, and relationships to memories of past experiences. There is a palpable feeling of connections when we remember, and legacy gaming practically makes that a game mechanic.

The Good:

Legacy gaming in the hands of a small group provides a place of connection. That city over there was founded when Steven rallied his force at the end of the game and marched across Asia to win! We thought we were all dead, but Amy drew the perfect card and we were able to discover a cure by the end of the month! Relationships that may have started minutes before that first game are quickly filled with stories to build on. What starts as game stories can turn into meaningful relationships just by investing in the lives of the players. When we try to talk about the best friends of our past- think about how much of that conversation is about experiences.

Legacy gaming in the hands of a small group provides a place of connection. That city over there was founded when Steven rallied his force at the end of the game and marched across Asia to win! We thought we were all dead, but Amy drew the perfect card and we were able to discover a cure by the end of the month! Relationships that may have started minutes before that first game are quickly filled with stories to build on. What starts as game stories can turn into meaningful relationships just by investing in the lives of the players. When we try to talk about the best friends of our past- think about how much of that conversation is about experiences.

When I talk about a friends of mine from college, the stories talk about bike rallies in the apartment and forty-eight-hour marathons of Grand Theft Auto, but it doesn’t take long for me to remember the times we wept together and spent hours praying through darkness. When I talk about one of my best friends from seminary, I’ll start with long games of Catan and quoting old internet cartoons – but the stories end with me recounting the day he literally had to talk me down from the ledge. The times where we laughed and had fun may be the first that come to mind, but they were just the gateway to the moments that drove us together.

It’s about laying down the blocks until you can look up and see the building standing in front of you.

The Bad:

The problem with legacy gaming in a ministry context is that it can have an insulating effect if you aren’t careful. When a game only has one narrative thread, there is a strong desire for the same group of people to be behind the wheel of the story. It’s hard to let go and let somebody else, especially somebody who wasn’t there from the beginning.

There are ways around this. Play in teams, letting each decision be tackled by committee. It may make the turns go longer, but that too can be mitigated by a time limit or an understanding of majority rule. No matter what your methodology, you’ll need to come up with some method of integrating more voices and new players. As long as you hold the game with a loose hand, you’ll be able to discover away around the problem.

The Ugly:

Playing with shared history can be a double-edged sword. The same power of memories to be the foundation of beautiful relationships can also salt the earth and ensure that nothing will ever grow. If you are not ready to deal with this – it can do some real damage to your ministry.

I have a growing collection of spoiler-free stories about Pandemic Legacy sessions. Amidst the fog of vagueness and euphemisms is one overarching truth. At some point everything will go bad. There will be months (each game session is a month of the calendar year) where you will lose, and a loss in this game can have weighty consequences.

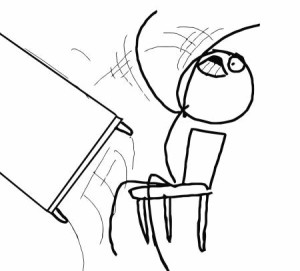

In this environment, you have to be ready to weed out grudges and blame at the root. Otherwise they might grow and fester, choking out any potential for good. Using such strong wording may sound like an overstatement, but it’s a definite possibility. I’ve known gamers, and you may have as well, who get more than passionate about winning. Problems like alpha gaming,* king making,** tanking a game, and the ever-infamous table flipping are all a result of people feeling hurt over another player’s choices. Much like the previous issue, this can be mitigated by a number of options depending on what works best with your group. It just comes down to knowing that it may be an issue and having a plan to deal with it.

In this environment, you have to be ready to weed out grudges and blame at the root. Otherwise they might grow and fester, choking out any potential for good. Using such strong wording may sound like an overstatement, but it’s a definite possibility. I’ve known gamers, and you may have as well, who get more than passionate about winning. Problems like alpha gaming,* king making,** tanking a game, and the ever-infamous table flipping are all a result of people feeling hurt over another player’s choices. Much like the previous issue, this can be mitigated by a number of options depending on what works best with your group. It just comes down to knowing that it may be an issue and having a plan to deal with it.

***

After weighing the possibilities, I think the potential for growth and foundational memories outweigh the potential problems. With T.I.M.E. Stories coming out with new modules with regularity, Pandemic Legacy boasting its ‘Season 1’ subheading, and the long anticipated Seafall due to come out this year … maybe it is time you evaluate whether legacy gaming will have a place in your ministry setting.