The Bioshock Infinite video game opens with you taking on the role of Booker Dewitt, a psuedo-noir style detective swimming in gambling debts and alcohol. Looking at the note that put him where he finds himself, his role is clear. Bring us the girl and wipe away the debt. He is about to enter Columbia, a floating city in the sky unveiled at the 1893 World’s Fair as a utopian civilization, and retrieve the girl named Elizabeth who is being kept there. I’d tell you more – but that would unravel the whole story that this game will try to weave, and that story is worth experiencing for yourself.

The Bioshock Infinite video game opens with you taking on the role of Booker Dewitt, a psuedo-noir style detective swimming in gambling debts and alcohol. Looking at the note that put him where he finds himself, his role is clear. Bring us the girl and wipe away the debt. He is about to enter Columbia, a floating city in the sky unveiled at the 1893 World’s Fair as a utopian civilization, and retrieve the girl named Elizabeth who is being kept there. I’d tell you more – but that would unravel the whole story that this game will try to weave, and that story is worth experiencing for yourself.

You’d think that these two would play a large part in the game play of the Bioshock Infinite board game, The Siege of Columbia. Maybe both players start together in the tower where Booker discovers Elizabeth? Booker would have offensive abilities to clear away enemies and obstacles in their path. Elizabeth would use her powers to create supplies and allies that would help them on their quest to flee the city. Seeing as one of the flaws critics have with the video game is the clunky combat that distracts from storytelling, that sounds exactly what people would want. Except it’s not even remotely what happens.

Oh, Booker and Elizabeth are involved in the board game. Each turn they’ll move around the board. Occasionally you’ll get a bonus if you capture Elizabeth, or Booker will rain destruction your troops. More often than not, though, they’re just passing through. You’ll hardly even know they were there. Their story barely even affects your strategy. If anything, the characters upon which the entirety of the source material is hung are more problem than protagonist.

Oh, Booker and Elizabeth are involved in the board game. Each turn they’ll move around the board. Occasionally you’ll get a bonus if you capture Elizabeth, or Booker will rain destruction your troops. More often than not, though, they’re just passing through. You’ll hardly even know they were there. Their story barely even affects your strategy. If anything, the characters upon which the entirety of the source material is hung are more problem than protagonist.

This game takes place during the video game’s climax, though you have no need to fear. There’s nothing in the board game that will give away the plot or will require you to have knowledge of the source material in order to understand. Not knowing much about the video game might actually help as you’ll have no expectations for what’s about to happen.

Columbia is in turmoil. Two factions – the Founders (the leaders of Columbia) and the Vox Populi (a revolutionary group that seeks to depose them) – are doing battle for control of the city. The players take control (or team up to control a side for the four player game) of either of these factions. The goal of the game is to march your forces across Columbia, conquering territories and gaining victory points by controlling whole sections of the city. The first person to collect ten points wins the game, having overwhelmed their opponents.

When this game was released back in 2013, I remember standing along the tables at the Plaid Hat Games booth. Every table was full, so I stood there trying to spy an opening. None came.

When this game was released back in 2013, I remember standing along the tables at the Plaid Hat Games booth. Every table was full, so I stood there trying to spy an opening. None came.

I was eventually jumped into a different game. I enjoyed it, but I’d lost my opportunity with Bioshock. When I finished playing, I realized how much more I needed to explore at the con. I left and wasn’t able to get back.

It was only recently that I got this game in my hands, and I’m glad for the delay. If I played it back then, I may have been disappointed. The video game had only just been released months before, and it had a strong grip on my imagination. If I went into this expecting to see what I saw there on my table, I would have been vastly disappointed. I would have missed the point.

The game isn’t telling Booker and Elizabeth’s story, because it didn’t need to. The video game already did that. Their story happens as you play – but the focus of Siege of Columbia is the siege itself. Both sides are trying to do what they think is right for the city and its people. Both think the other is a villain that needs to be put down. Both think they are right and just before God and man, taking up arms against those who would seek to undermine freedom and truth. And both of them are terrified that Booker Dewitt will be the end of them all if he accomplishes his goals.

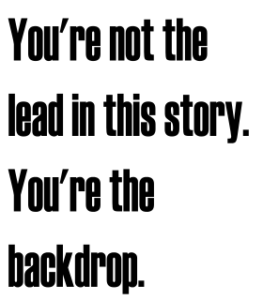

Regardless of which side you choose, you think you’re the hero of the story being told. You think you’re the focus. The champion. But if you look at the game from the perspective of the original narrative – you aren’t even close to a focal point. Comstock, Fitzroy and all the other potential characters you play in this game are all antagonists in Booker and Elizabeth’s story. We find out about their history and perspective, but – during this scene of the video game- these forces aren’t much more than set pieces. You’re not the lead in this story. You’re the backdrop.

Of course we all want to be the hero. We want to be the person that everyone is reading about. I can’t say I’m not susceptible to it. My first draft of this article opened with stories about me playing the video game leading into that bit about me waiting in line to play the board game.

Of course we all want to be the hero. We want to be the person that everyone is reading about. I can’t say I’m not susceptible to it. My first draft of this article opened with stories about me playing the video game leading into that bit about me waiting in line to play the board game.

It was possibly the worst way to open, and yet I wanted my story to be the story. I waited three years for this game, looking at it like a little kid stares at the puppy in the pet shop window. Why wouldn’t you want to know about the struggle of a person you may never meet to get a game you may never play? … Oh yeah.

The silliness of this is even more pronounced as I look at this through my lens as a Christian. If I honestly believe that life and history is a story that God is unfolding over time – how presumptuous is it that I think my part in that story is the highest value? That I’m owed a happy ending and that my struggle will all work out in the end?

We Christians love to site verses like Jeremiah 29:11 that says “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope” – but hate to talk about the context. The context of that verse is God speaking through a prophet talking to a stiff-necked and stubborn people about to enter into generations of forced slavery and servitude. It’s a reassurance that He has not left them even as they are about to enter into pain and suffering that some of them won’t ever leave in this life.

We love to talk about heroes of the faith, but imagine that their lives are filled with tangible blessings as a favored son or daughter. We don’t want to talk about folks like Dietrich Bonhoeffer who said, “Silence in the face of evil is itself evil: God will not hold us guiltless. Not to speak is to speak. Not to act is to act” and had his life cut short in a concentration camp for choosing to act against the Nazis.

We’re focusing on the wrong protagonists. Our stories are important to God, but everyone has a story that’s going on in tandem with our own. Their story is just as important. They’re all a part of the larger narrative He’s telling. When we think that our story is the only one worth telling – we twist it. When we see our story doesn’t pan out how we want – we think less of God, making Him out to be uncaring or powerless. We fail to realize just how many stories are out there and how the paths cross. We forget who the hero really is.