I had read the reviews, seen the components, but I had yet to sit down with the game. It was set to be the featured game at the next day’s charity event, and I knew that I needed to wrestle with the mechanics if I was hoping to teach it to others. The game’s design allowed for it to be played solo. I could get elbow deep into its nuances before it ever hit the table – but the lid stayed shut into the evening. I distracted myself with last minute preparations instead. Perhaps I’m still delaying it even now. The game is Freedom: The Underground Railroad – designed by Brian Mayer and published by Academy Games.

I am not often one for “cube-pusher” games. The sort of experience that often breaks down to “I move this cube here which lets me pick up these different cubes there” does not excite me. So when I cracked the lid, I was not pleased to see the host of huddled, rattling wooden cubes staring back up at me. I set up the board as laid out in the instructions, and settled in to what was probably going to be a long, dull experience.

I am not often one for “cube-pusher” games. The sort of experience that often breaks down to “I move this cube here which lets me pick up these different cubes there” does not excite me. So when I cracked the lid, I was not pleased to see the host of huddled, rattling wooden cubes staring back up at me. I set up the board as laid out in the instructions, and settled in to what was probably going to be a long, dull experience.

I could not have been more wrong. Not only did I find the game riveting – but the cubes were a lot of the reason why.

The basic premise of Freedom is that the players are abolitionists, working together to end slavery in America. The goals are two fold. Get as many cubes as you can to freedom in Canada, and raise enough support to end slavery for good. If you lead all of the cubes to freedom but don’t end slavery – the boats will just be back tomorrow filled with more cubes to be added to the board. If you end slavery, the boats might have stopped, but you’ll be looking at a full track of “lost” cubes, walking through the aisles as you contemplate the costs.

There is a a pivotal moment in this game that actually has little to tangibly do with this game’s play. You may find yourself fiddling with the unpainted cubes, running them back and forth over your hand absentmindedly. Whether it builds with time or hits you like a hammer, it is the moment when you remind yourself that these cubes are people.

There is a a pivotal moment in this game that actually has little to tangibly do with this game’s play. You may find yourself fiddling with the unpainted cubes, running them back and forth over your hand absentmindedly. Whether it builds with time or hits you like a hammer, it is the moment when you remind yourself that these cubes are people.

Every day the ships dumped more cubes. If I didn’t move, the leftovers would just become lost. While the game doesn’t go into depth on what it means to be “lost” – it makes it quite clear that cubes that end up there are not coming back into the game. There is nothing that can bring them back. These cubes, these people, were trying to find freedom from a life trapped between staying in brutality and shame or death on the road at the hand of the slave catchers. Either way, their state seems hopeless.

I started to wonder why the designer had chosen to use the cubes. There are certainly practical reasons. Cubes are cheap, easy, and fit well in a box. But as I moved them about the board, there was an underlying power in those simple shapes. These people, these cubes, were seen by their owners as nothing more than property. The ‘lost slaves’ track could become nothing more than a tally of misplaced inventory.

It is easier to have a level of detachment when you remove someone’s humanity. A cube can’t love, hate, or desire. It just is. If you don’t have enough of them – you can always get more. Whether intentional or not, the fact that the board was becoming overwhelmed with shuffling cubes stirred me. My heart leapt every time one of them crossed the border into Canada. I felt a cold sort of darkness when the slave catcher moved into a spot on the board that brought me two cubes closer to losing the game.

It is easier to have a level of detachment when you remove someone’s humanity. A cube can’t love, hate, or desire. It just is. If you don’t have enough of them – you can always get more. Whether intentional or not, the fact that the board was becoming overwhelmed with shuffling cubes stirred me. My heart leapt every time one of them crossed the border into Canada. I felt a cold sort of darkness when the slave catcher moved into a spot on the board that brought me two cubes closer to losing the game.

As an American – this is part of my history. It is a horrifying era that I wish wasn’t carved into the past of the land I call home. Yet when I suggest this game should come out, the awkward tension that hovered around the table reminds me that there is an element of this game that is too real, too present. When I asked my friend if he would like to play, he responded, “Man, yeah I’ll play. It might strike a little close to home, but I’d rather my son know that this happened than avoid the awkwardness of it. This is my history – and it wasn’t that long ago we were still dealing with all of this.”

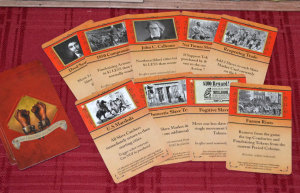

Freedom is an entertaining cooperative strategy game that is challenging, yet beatable. It is a tight collection of moving parts that come together in an engaging experience. As an educational tool – it’s filled with people, places, and events taken directly from the pages of history. The game’s text lived alongside the quotations, descriptions, and statistics – each informing the other. But this game earned its place in my library because I could not run from those cubes. I could only promise to remember them – and remember that they aren’t just cubes.

Thanks for this – I’m really interested in games like this that create learning opportunities without being pedantic. I’ll have to check it out.

Your description gave me goosebumps. Now I Need this game.

This is a phenomenally well written article.