I was in a hotel lobby in Indianapolis. At a table in the corner, a handful of gentlemen gathered around a board emblazoned with images of Arthurian legend. The Lady of the Lake held aloft Excalibur – if just out of reach. The grail was being elusive, but the brave knights pressed on towards our goal. The walls of Camelot were being besieged on all sides, but the foes were being turned away. That is, until Sir Trystan sold us out to the Picts.

Like other games

of

this

sort

– Shadows Over Camelot

has all of the players appear to be striving towards the same goal. Yet, like the proverbial wolf among lambs, there are forces among them that would seek to undermine these noble heroes at every turn. They are the traitors, and their victory depends on your defeat.

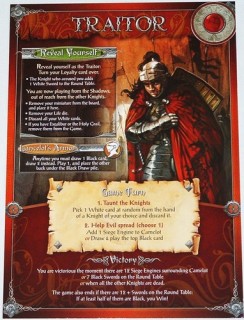

The term “traitor mechanic” is applied to cooperative games that have one or more players whose victory condition is in opposition to the rest of those playing the game. In Shadows, the presence of a traitor can be hidden until they are discovered by the others, revealed by the traitor himself, or held in secret until victory is declared.

The term “traitor mechanic” is applied to cooperative games that have one or more players whose victory condition is in opposition to the rest of those playing the game. In Shadows, the presence of a traitor can be hidden until they are discovered by the others, revealed by the traitor himself, or held in secret until victory is declared.

All it takes is that hint. That subtle suggestion that one of you at the table might possibly be a traitor starts the wheels turning. You may call into question whether another player is the acting against you or just bad at the game – so you start watching him closely. You might observe that the player across the table from you has not made eye contact once during the game – her eyes locked on the board. Clearly that behavior is representative of a traitor. You’ll have to keep an eye on her too. Before long, you could feel like the entire table might be the traitor, and every play feels one step closer to inevitable betrayal.

the traitor revealed!

In Shadows Over Camelot, the knights must complete certain heroic deeds by playing cards from their hands. Only one action can be done per turn, so everyone is relying on the others to work towards the group’s benefit in order hinder the progress of evil. When trust is held on such a fine edge – can you accept that the advice you are being given is accurate? If the other player doesn’t follow through – was he leaving you to fail or just dealing with some new threat? What if it’s all just a lie designed to subvert the kingdom?

I’ve seen games with traitor mechanics implode in on themselves with fear. The players become so worried that they can trust no one that their victory slips from their fingers to one of the many loss conditions. But it’s just a game, right? There’s no reason to fear in the real world. But what happens when we search the shadows looking for traitor? What does the world look like when we’re made to feel that a traitor is waiting around every corner?

When the traitor mechanic invades the broader world, it is subversive in a much more insidious fashion. There is no one building siege engines at the gates. There does not need to be anyone there at all. The fear of someone being there is enough. If we fear the traitor, we retreat from our neighborhoods – seeking to protect our own from the dangers outside. If our fears drive us to hunt out the villain – we will cut off the very hands and feet of Christ to carve ourselves into the likeness of our church leadership. We are driven into exile by our fear of attack.

The most interesting aspect of Shadow’s traitor mechanic is the fact that in any given game, there may not actually BE a traitor. The cards are dealt in secrecy. While the traitor is always a possibility – there is no guarantee. With only one heroic action a turn, the players can waste precious time accusing each other in a race to root out their enemy, only to find out that there was no enemy besides the ones outside the walls. The hunt we set out to lead for assurance of victory can become the very thing that brings about our defeat.

In a dearth of traitors – we spend our time creating them. We might even become them.