The Reformation has always been an intriguing period of history for me. My fascination peaked in college. I stood at the door of Schlosskirche in Wittenberg Germany. I was there on a tour, hoping to garner church history class credit in a far more enjoyable way than sitting in lectures. It was there, in 1517, that Martin Luther nailed his ninety five theses – a list of academic disputations against doctrine and practices he felt were abusive. He declared that no amount of indulgences bought or penance endured could forgive sin, but that faith in Christ alone – Sola Fide – was sufficient. How could such a time of spiritual, personal, and civic upheaval be encapsulated in a lightweight, two-player, area control game? I was excited to find out.

The Reformation has always been an intriguing period of history for me. My fascination peaked in college. I stood at the door of Schlosskirche in Wittenberg Germany. I was there on a tour, hoping to garner church history class credit in a far more enjoyable way than sitting in lectures. It was there, in 1517, that Martin Luther nailed his ninety five theses – a list of academic disputations against doctrine and practices he felt were abusive. He declared that no amount of indulgences bought or penance endured could forgive sin, but that faith in Christ alone – Sola Fide – was sufficient. How could such a time of spiritual, personal, and civic upheaval be encapsulated in a lightweight, two-player, area control game? I was excited to find out.

Literally seconds after someone in our community shared the listing on Board Game Geek for Sola Fide, I was writing an email to the folks at Stronghold Games to see if we could get a copy. It’s a rare opportunity that I can say to a publisher that our community would have a unique interest in one of their titles – but a game set in such a pivotal time in the history of the Church would be among them. I received word that I’d be getting a copy, and I began finding players long before it arrived. The play time was right. The theme was rich in historic lessons while not seeming heavy-handed about it. The game is even part of Stronghold’s Great Designers Series – coming from Jason Matthews (Twilight Struggle) and Christian Leonhard (1960: Making of a President). There was no way it could fail. And it didn’t – for the most part.

When we review a title, we don’t often breakdown every bit and quirk of the game. We talk about the experience of playing and the deeper levels of impact they have on us while playing them. In this instance, however, I can’t get to that deeper level without breaking down some of the specifics of the good, bad, and indifferent. In looking at its use of the theme, its game play, and even its faults – I came out with an oddly personal reaction.

When we review a title, we don’t often breakdown every bit and quirk of the game. We talk about the experience of playing and the deeper levels of impact they have on us while playing them. In this instance, however, I can’t get to that deeper level without breaking down some of the specifics of the good, bad, and indifferent. In looking at its use of the theme, its game play, and even its faults – I came out with an oddly personal reaction.

Theme

Going into the game, there were two things I wanted to see from this theme. My family faith is deeply entrenched in Catholicism, while my education and ministry is firmly Protestant in nature – painting either in superior light to the other is troublesome. I also wanted to see if the theme was integral to the experience or just a veneer laid over top of the mechanics.

The cards in Sola Fide are filled with people, places and events that were influential in the historical context of the Reformation. I appreciated cards about disagreements between the reformers. I

saw cards like the Diet of Worms and recounted being on the same spot Luther stood. But I brought that too the game. Little of that history was in the game itself other than in a companion book that was never opened once in any of my games.

Theme wasn’t integral, but it wasn’t missing either. It appeared in a nuance I appreciated. The Catholic player’s deck, for instance, contained more cards that pertained to the nobility side of the tile, while the Protestant deck favored the commoners. The Reformers’ early successes were often in the hands of the common man. They thrived by teaching literacy and making the text of scripture, previously only available to the priesthood and the well off, widely available via the printing press. The Catholic Church stood on generations of sway in the nobility both in the spiritual and political world.

A number of these subtleties also remind us that neither side of this game is uniformly heroic or villainous. They are people, and there are abuses, conflicts, and shameful turns that accompany every good and noble ideal on each side. For every military battle card, there is a humble saint who sought peace. For every noble stand for the common man, there was a boorish insult mascarading as an academic disputation. It succeeds, in this regard, even if it’s hidden.

Gameplay

Sola Fide involves playing a card on your turn to manipulate various Imperial Circles (game tiles) in a couple ways. You mostly have some combination of converting people to your cause, manipulating who the dominant power is in the region (the nobility or the commoners), and moving the ‘disputation token’ to possibly gain a bonus point for collecting that region. When you have converted every space on the dominant side of a tile to your side, you capture that tile, revealing any tile under it that has been hidden, and gaining one of the foreign influence cards for a bonus action.

If this game has a failure, it’s here. It is impossible to play this game avoiding a scenario where there’s only one tile in contention for the two players. As the game doesn’t end until all of them are collected, there will be a run of turns where you convert one person to your side, and your opponent converts them back. You manipulate the dominant force, and they move it back. It’s a tug of war that can drag on.

If this game has a failure, it’s here. It is impossible to play this game avoiding a scenario where there’s only one tile in contention for the two players. As the game doesn’t end until all of them are collected, there will be a run of turns where you convert one person to your side, and your opponent converts them back. You manipulate the dominant force, and they move it back. It’s a tug of war that can drag on.

This can be pronounced if you play with the optional card drafting rules. Drafting your deck for the game allows for a change up in game play for an otherwise static board and adds unique strategies to the game. As such, the gameplay encourages you to play with the draft as soon as you can. Yet it is important to finely balance a draft in order for the deck to function properly. I played one game where I neglected to pick up any cards that moved the dominance to the commoner side. There were several tiles where I owned that side while having no tools to actually claim them, and I didn’t know it until the game was mostly over. Team that up with the fact that claiming a tile provides a bonus (even if it is less than game breaking), and it is easy to have a run-away game leader.

All of this is true, and I’m hardly the only one saying any of it — but I still really enjoy the game. While these snags prevent me from wanting to add it to our InnRoads Approved list, I can’t say I don’t like it.

Here I Stand…

This is a tragically flawed game. I’ve had equal parts enthralling and infuriating experiences, and it doesn’t hit my table with the enthusiasm I hoped it would. But I can’t walk away from it. Yes, it is possible to have a run away lead, and, yes, a bad draft will lead to a less than stellar experience. But I’ve also never had a game last longer than the advertised forty five minutes – either by its completion or a mutual understanding of stalemate – and I’m more forgiving of a less than perfect play session if I can quickly move on to one that I will enjoy.

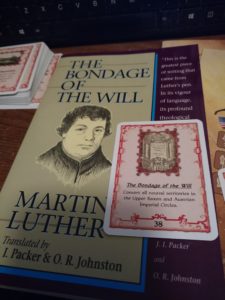

The theme is largely window dressing over bare mechanisms – but it’s window dressing in the style of an artistic Macy’s Christmas window display. There’s a chance that it might not be your thing, and therefore there’s nothing available that will change your mind about the grinding gears of the mechanisms. But there are others, like this church history nerd who posted a picture to BGG of his copy of The Bondage of the Will with the card of the same name, who can overlook the troublesome elements for the chance to share where world history and my history met in Wittenberg Germany.

The theme is largely window dressing over bare mechanisms – but it’s window dressing in the style of an artistic Macy’s Christmas window display. There’s a chance that it might not be your thing, and therefore there’s nothing available that will change your mind about the grinding gears of the mechanisms. But there are others, like this church history nerd who posted a picture to BGG of his copy of The Bondage of the Will with the card of the same name, who can overlook the troublesome elements for the chance to share where world history and my history met in Wittenberg Germany.

At the Wittenberg door, I thought about my own reformation in microcosm. I had a moment where I stood before my dad and said that I would no longer be considering myself a Catholic. I had come to faith, real faith, for the first time in my life – and it was in a different church. I was leaving behind the church of my father and his father before him, and it was the first time I ever honestly fought with him. It took years before the wounds that ripped open there were healed. Took a couple years before Dad said he was proud of me for pursuing faith the way I did. A couple years before I realized that just because I never found faith in the Catholic Church, didn’t mean his faith wasn’t just as real as mine. And there I stood, listening to the echoes of generations who saw that door as place where war was declared. In a way, this game reminded me, that there will be complications, differences, and downright anger – but there is something that will help you overlook them all if you want to look for them.